— Written by Samuel Kuhn —

So, the summer is coming to an end, and I have faced off against a behemoth of a challenge. The readiness potential has proved elusive at every turn. I have tried different hardware, software, different electrode locations and experimental locations, different participants with different hair lengths, and yes, I even shaved my head to find this signal… no dice. Weeks and weeks of consistent effort have led me to only one clear conclusion: the readiness potential is NOT easy to detect in single trials.

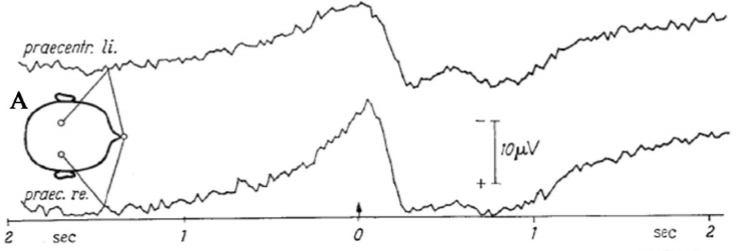

The allure of this project from the outset seemed so clear to me: let’s try to make a device that can use the electrical activity in your brain to predict when you are going to move. The electrical activity of interest in this case was the readiness potential that Kornhuber, Deecke, and Libet, all world-renowned scientists, built their careers upon. All for one silly little squiggle with a bump in it!

And even though this signal has a history longer than my own life, I have had no clear success in replicating it, but I’m not gonna let that stop me. In the face of such a challenge, I have had to grow as a scientist in order to make progress. Because I haven’t been able to replicate the Readiness Potential, I have pivoted into trying to explain some of the science behind the Readiness Potential.

Here’s what have I been doing recently.

In trying to take this new scientific approach, I have tried to identify possible alternative explanations for the signal known as the Readiness Potential. There are two main confounds that I am exploring: the influence of an internal countdown, and the influence of a response cue. You see, I think that the signal that seems to show up in Readiness Potential experiments, is not directly related to the use of free will to make a decision.

I think that instead, the signal that precedes movement in these experiments may be related to the subject forming a habit of counting down to a movement as opposed to just moving the instant they decide to move. The important factor here could be the countdown or it could just be the anticipation of getting ready to do something. That doesn’t mean that when you anticipate doing something you will do it. This gives me another thing to test in my experiments; how does the anticipation we feel compare with the Readiness Potential?

There are so many ways to explore the things I’ve listed here, but I have settled on a specific set-up so that I can minimize confounds in the experiment and maximize reproducibility. My lab notebook has a detailed explanation of my thinking on how I’m setting up this experiment if you’d like to read further into my thought process. Also, eventually I hope to write up the results of this experiment in a formal manuscript and submit the manuscript to a scientific journal.

I may run out of time this summer before I can do all of this, but that is okay, because once I have the data collected, I will have the ability to analyze it after the fact. The only thing I won’t be able to do at that point is improve the quality of the data.

What this internship meant to me

Nevertheless, I have had a million and one great experiences while I’ve been here at BYB. I have learned things I didn’t think I was capable of understanding (micro-electronics). I have practiced things I thought were beyond the scope of my abilities (soldering/presenting data daily). I’ve had more courage while I’ve been here at BYB; the courage to try things other people might think are impossible. And you know what, sometimes those things are not possible, like predicting movement with the Readiness Potential! But sometimes they are! The best thing I have learned here is just that you don’t really know what’s possible or impossible until you try.

So, to all those scientists in training, to all those whose eyes widen when they look at the sky, don’t shy away from the impossible. Go find out for yourself!