Oh hey there! Long time no see, why don’t you have a seat and hear what I’ve been up to since my last blog update.

If you were at the Ann Arbor 4th of July parade you might have seen me dressed up as a beautiful purple octopus (or maybe it was a squid? The costume was quite ambiguous). The costume was an elegant combination of recycled foam, acrylic paint, paper mache, and hope.

For the behavioral analysis part of my project I have decided to forgo maze solving, as forcing an octopus to run a maze over and over for data proves both more difficult than previously thought and honestly doesn’t seem that fun for the octopus itself.

Instead, I have decided to delve deeply into deciphering the ancient mystery of Octopus wrestling. Believe it or not, if left to their own devices, bimac octopuses absolutely love to have wrestling matches, pushing around their opponent with their tentacles to figure out who among them is truly the dominant bimac. They then take a short break (only a couple minutes at max) and go back at it again, in a rematch to see if the underdog can take a round off the reigning champion.

Before you get too worried for the safety of our small aquatic friends, know that I’m not forcing or aggravating them into wrestling and that it’s actually quite difficult to prevent them from tusseling. Additionally, I keep a close watch on them to make sure no one is trying any dirty tricks like biting or going for the eyes.

This unique behavior prompted me to laser cut some custom housing arrangements for these 8 legged boxers. They are very territorial, so I had to construct some acrylic dividers with nylon mesh windows to promote water circulation. I inserted these into their aquarium to separate it into three individual tanks for the octopus because I’d prefer them not to fight unsupervised.

Next, to film the matches I constructed an acrylic wrestling chamber with a rack to hold the video camera for recording. This way they have an area to fight and my camera is guaranteed to give me the same angle of video every time.

I mount a go-pro facing directly down into the white, open-faced tank. This way I get identically framed footage every time, very important for later analysis

There are many intricacies to an octopus wrestling match, many behaviors and patterns that we can try to decompose and comprehend with the help of computation. They circle each other, they taunt their opponent with their curled tentacles, they sometimes even act almost coy towards each other. This is where I switch to a completely different animal, Python, to analyze the speeds, positions, angles, and even colorings of the octopuses.

Why won’t you Look me in the Eyes?

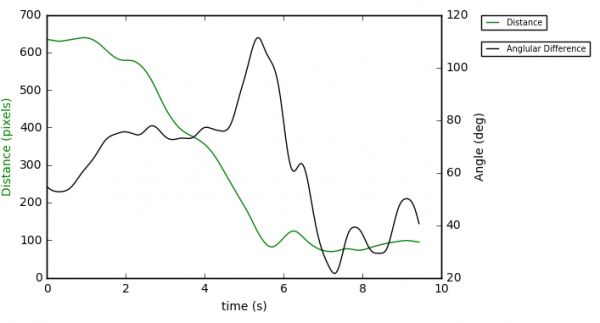

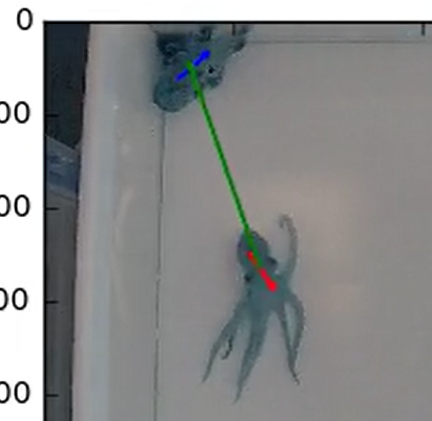

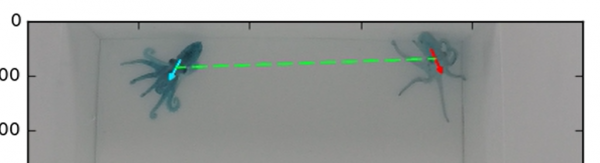

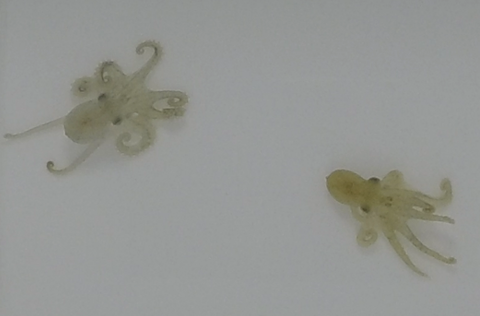

Our confidently wrestling octopuses seem to have a bit of a shy side when it comes to making eye contact with each other. As you can see in the two frames from footage recorded of the octopuses before a wrestling bout, they do not appear to be facing each other at all, and watching the footage confirms this; they approach one another by moving sideways, not with their tentacles leading the movement as one would expect.

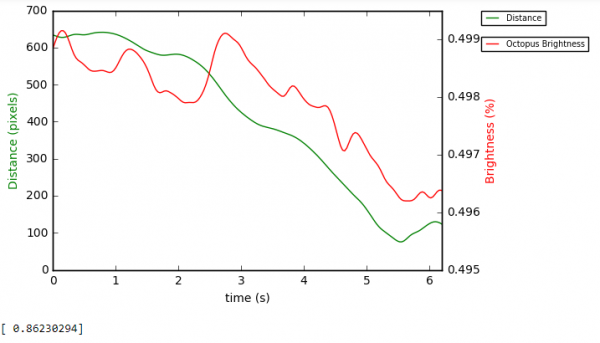

This however drastically changes as the distance between them closes, as seen in the above graph, as the distance lowers beyond a certain point, the angle between the two octopus rapidly drops to zero (zero meaning they are directly facing each other).

This seems to indicate a certain “fight zone” or, dare I say, a “danger zone”, where if the distance between the two enters this zone they will rapidly spin around to face their opponent with tentacles at the ready. This is most curious since it’s not only octopuses that display this kind of behavior.

Link to Gorilla Fight: Keep an eye out for how they approach eachother at a weird angle…

Even Silverback Gorillas tend to go into a fight sideways, spinning to face their opponent at the last moment of their approach, and black iguanas are suggested to use eye contact and approach to discriminate risk from an approaching animal (As described in the 1992 paper Risk discrimination of eye contact and directness of approach in black iguanas by Joanna Burger).

Octopuses: Maybe not as Bright as we Think

No, I’m not talking about their intelligence, of course, the octopuses we have are plenty smart, even though they sometimes seem to forget what exactly to do with a crab we give them for food, deciding to instead stare at them for a while. I’m talking about their physical coloring, their chromatophores.

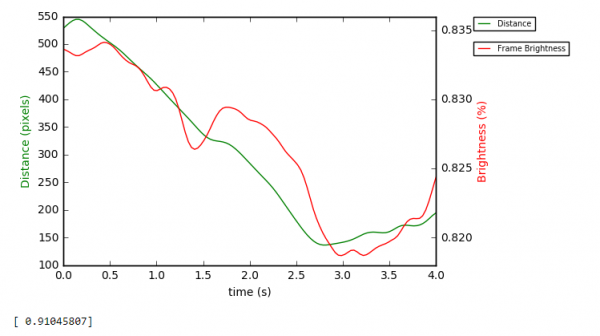

Their coloring is an extremely reliable way to know if you’re coming too close towards them. Even when they’re still in their tank, if you quickly approach the glass they will drastically darken their color, hoping you leave them alone.

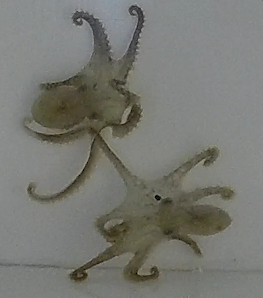

When there’s a fair bit of distance between the competitors, they both appear to be a shade of light beige, but once that distance closes and we enter the “danger zone”, the one going on the offensive colors its tentacles a dark brown before entering the active wrestling bout.

In the pictures below we can identify the attacker and defender by their relative colorings, the bottom octopus flaring up with color in its first offensive, and then the top one flaring up in retaliation.

I’m Bored Already, So What and What’s Next?

If we can confidently identify parallels between these octopuses and other non-cephalopod animals when it comes to approaching and commencing a fight, we might be left with a great assay tool to study the physiological and genetic influences on this behavior. Bimacs are quite ubiquitous and easy to care for animals, and so finding such a use for them would help make neuroscience a more accessible topic for audiences outside of research laboratories, since even a high-school student can take good care of a bimac octopus.

I’m now working on a program that uses convex hulls to draw a contour surrounding the octopus, in order to get a bearing its relative size and tell us more about what it’s doing with its tentacles. A tightly curled up octopus will have a very small contour, whereas a more freely spread out one will take up a much larger area with its contour. This might prove to be interesting information when it comes to analyzing the initiation of the wrestling matches where there is a lot of shape changes in the octopuses.

Additionally, I’m hoping to gather enough data in the next couple weeks to show real trends in the octopus behavior and run more general analyses on the full collection of vectors. This will let me say more confident statements on the overall behavior of the bimacs.