What follows is a tale of customs adventures, personal legal status in a foreign country, and the history of Serbia and Yugoslavia.

We have had the grace to work in Serba a number of times over the past few years, and 2024 was no different. During July, we were invited by the Center for the Promotion of Science (CPN) in Belgrade, Serbia, to run a Brain-Machine-Interfaces workshop with a group of ~20 talented Serbian high school students.

Many of us were staying in the “BYB Barracks”—a beautiful AirBnB that would have been nice for 2-3 people but was a little cramped for 5, on the famous Knez Mihailova street (24 Knez Mihailova, to be exact). When we arrived at the AirBnB, the owner of the apartment, Sanvila Popovic, greeted us in a very friendly, gracious way. When I asked her if she was Serbian, she replied: “Yes, I was born in this building, and my grandfather was an architect who designed this building as well. His name is Branko Popovic, and you can read about him on Wikipedia. He was a bit of a polymath: an architect, the dean of engineering faculty at the University of Belgrade, and a surrealist painter. Unfortunately, with the rise of the communist party in Yugoslavia, he was arrested and killed for his political views in 1944. I never had the chance to know him.”

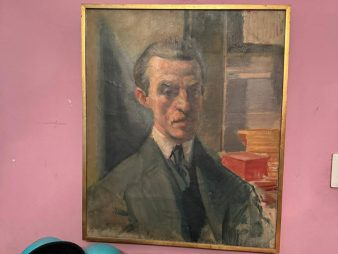

Given such an interesting, tragic, and personal story that she shared with us, we became text-message friends with Sanvila, exchanging messages about Serbian culture, things to do in Belgrade, and even texting her when we visited the National Gallery in Belgrade and saw some of the paintings of her grandfather Branko.

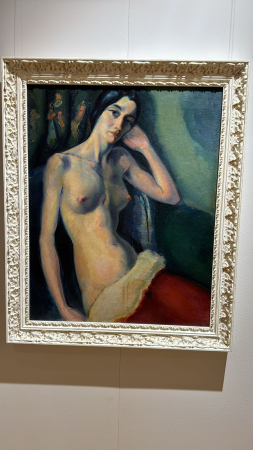

The portrait on the left is a famous self-portrait of Branko, and the portrait on the right is… Well, we texted Sanvilla and asked who the woman in the portrait was, and her reply:

“I think this is Angel Gaston (French), the first woman of my grandfather, before he met my mother.”

Back to engineering.

The fellowship was a mix of our own research on new upcoming products (stay tuned) and working with the new students on interfaces with the MicroBit controller. As part of this process, we also wanted to order some wireless enabled circuit boards from Italy (from Arduino, you have probably heard of it) for some other R&D.

How to Get a PCB (Printed Circuit Board) into Belgrade, Serbia

When we ordered the circuit boards from the Arduino online store, we assumed the equipment would arrive on time during the two-week fellowship period in Serbia. To the west of Serbia is Croatia, then Slovenia, and then Italy. The distance from Belgrade, Serbia to Monza, Italy (the HQ of Arduino), is approximately 1,000 km (620 mi), only a 10-hour road trip by car.

But as we all know, when goods travel the world, it´s not the distance that matters but the sovereignties involved. On July 1 (Monday), we ordered the gear from our laptop at the CPN and proceeded to track the package. On July 2, the package left Gattatico, Italy, and on July 3, 2024, subsequently arrived and then left Koeln, Germany. On July 4, the package also arrived and left on the same day in Velika Gorica, Croatia. Moving fast. The circuits arrived in Belgrade on July 5th, and were declared “delivered by UPS” by the online tracking service.

Except that they weren’t. We had no circuits in our hands. Strange, no?

On July 5th, UPS called our friend and colleague at the CPN, Katarina Stekic. Her number was registered with the package as she is Serbian and speaks the language, and UPS told her more information was needed before delivery could be completed. Specifically:

- A signed document (by me), explaining what the packaged contents are, with a description in Serbian (the interns helped us with that), and a statement that I alone would be using the goods and not giving it to someone else (one wonders why that would matter – ever heard of birthday presents?).

- The proof of purchase from the Arduino Website

- The proof of credit card transaction from our AmEx credit card website

- A copy of my Serbian ID or otherwise proof of me being in Serbia legally.

BYB is used to international shipments, so documents 1-3 could be prepared in 30 minutes. If you want to practice your Serbian, this is what we wrote down for the package contents, thanks to the help of student Andrija Gajic: elektronske ploce koje su koriscene za pravljenje elektronskih igracaka.

Document 4, however, was tricky. Since I was only in Serbia for 2.5 weeks, I was in the country on a 90-day tourist visa. My legal status was thus as a tourist and not as someone living and working in Serbia. All I had to prove my legal status in Serbia was the entry stamp in my passport. What to do?

I wrote the situation to the customs broker Aleksa Gacic, and she said I could get a document at the police station stating that I was in the country legally. To follow the letter of the law, you are required to register your residence at the police station the moment you arrive in Serbia, but in practice it appears that not many people do it. If you are staying at a hotel, they usually automatically do it for you… But… I was staying with my team at an AirBnB.

Katerina helped me again and called our landlord Sanvila, who was surprised, saying that in 3 years of running the AirBnB, only one other person had asked for this document, but for a similar reason (a shipment). She said she was travelling for the weekend for a Balkan War remembrance event in Bosnia, but we agreed to meet up on Sunday night to head to the local police station together.

We met up on Knez Mihailova street outside the AirBnB and walked to the police station on 33 Majke Jevrosime. When we arrived at the police station, I tried to enter, but an officer became visibly agitated and wouldn’t let me pass. Evidently, you aren’t permitted to enter a Serbian police station with shorts on (pants only allowed). Sanvila talked to the police officer for a number of minutes, and the officer said they can’t issue the document without proof that she is the owner of the AirBnB and brings the contract/receipt showing that she bought the apartment.

Sanvila told me that she had changed her personal apartment (where she lives) recently, and things got shuffled around, but she would try to track down the contract. Two hours later she called me, said she had found it, and I returned to her apartment, which incidentally was directly below the AirBnB where our BYB team was staying. Serbian culture being Serbian culture, she invited me into her kitchen where we had some lemonade and chatted for a bit. I was able to meet her mom Dušanka (or Grandma Popovic, as I called her) and her son Vasilije who is going to University in the fall to study political science. Sanvilla also gave me a tour of her large apartment, which had some additional paintings of Branko.

After the tour and lemonade, we returned to the police station together. Once there, the police officer began arguing again with Sanvila, saying that the contract shows three owners: her, her brother, and her mother. Since there may be an unknown dispute between the owners about running the AirBnB, all three needed to come to police station before they could issue my legal residency document. All this absurdity for two Arduino boards.

Sanvila said maybe her brother and mom could come the following day. However, the next day was also her mom’s 84th birthday, and moreover, she has some mobility issues and is showing some early signs of dementia (but still not grave). I felt bad and thought all this was excessive, and I told Sanvila not to worry about it as it is too much work for 90 euros worth of circuit boards. Sanvila insisted multiple times it was no problem, that her family wanted to help us, and said she would text me in the morning when her brother and mother were ready.

Sure enough, I walked over to the police station around 11 AM on Monday morning and met with Sanvilla’s brother Stojan and their mother Dušanka, who I wished Happy Birthday and apologized for all this mess. She spoke French and Serbian, neither of which I speak, but the intent was clear enough. Stojan began speaking quickly with the police, showing ID cards and contracts. One got the sense that the police officers were giving Stojan a hard time, but being Serbian, Stojan knew how to handle it. Dušanka was subversively laughing at the whole situation with the liberty that senior citizens are afforded. After 45 minutes of waiting, we finally had the last required document. Achievement unlocked. Of course, we had to take a selfie.

With the document in hand, I returned to the CPN and e-mailed a scan of the document to Aleksa, the customs broker at UPS. She informed me that her team would review it, and it should be cleared within 1-2 business days. It was already Monday on the second week of the two-week fellowship, so I was running out of time. Nonetheless, on Wednesday afternoon, we received an email stating that the item had cleared customs, would be delivered the following day, and that I would have to pay the equivalent of 50 euros in Serbian dinars in cash to the delivery man.

Or, alternatively, I could come directly to the UPS facility at the Tesla Belgrade airport to pay and pick it up.

50 Euros in cash for a 90 Euro order? That’s a bit predatory in our opinion. High tariffs are usually designed to protect local industries (think electric cars currently in the USA and electronic components in the 70s/80s in Japan where governments used them to protect growing industries). There really isn’t, however, an electronics industry in Serbia to protect, so it’s just a short term source of revenue for the government at the expense of long-term growth for a country. You can’t be an electronics startup in a country if you have to pay >50% imports duties on any components you need.

Since the payment had to be in cash, and who knows when the delivery man would arrive at the CPN (what if I stepped out for a moment?), I decided to take a CarGo (the Serbian equivalent of Uber) to the UPS facility and pick up the package directly.

I have never worked so hard, and involved so many people, just to receive two Arduino circuits. But the circuits were in hand and we could begin to work on them. Final level boss of Serbian Customs Video Game Defeated!

The week ended, and the internship was a huge success (read all about it here). All the students ended up building really creative projects we could have never come up with on our own.

The fellowship at the end, it was time to say goodbye to Belgrade, Serbia for 2024. Sanvila graciously invited me to her apartment before my flight to have some Rakija, gossip about our personal lives, tell stories about Branko Popovic, learn more about Yugoslavia/Serbia history, and discuss some of the differences between Serbian Orthodox Christianity and Catholicism. In the end, the circuits weren’t nearly as important as making new friends. We will surely see the Popovic family again. Meeting wonderful people while doing creative things—one does not need much more in life.

PS: If you want to learn more about Branko Popovic, Vasilije wrote up a report for his school work which is much more extensive than our write-up here.