-

FellowshipI write this on the last day of the fellowship. With a really heavy heart. Eleven weeks went past really fast. Although I shall be back again in Ann Arbor for school in September, it won’t be the same. This was one of the best summers I’ve ever had. I will surely miss everyone at […]

FellowshipI write this on the last day of the fellowship. With a really heavy heart. Eleven weeks went past really fast. Although I shall be back again in Ann Arbor for school in September, it won’t be the same. This was one of the best summers I’ve ever had. I will surely miss everyone at […] -

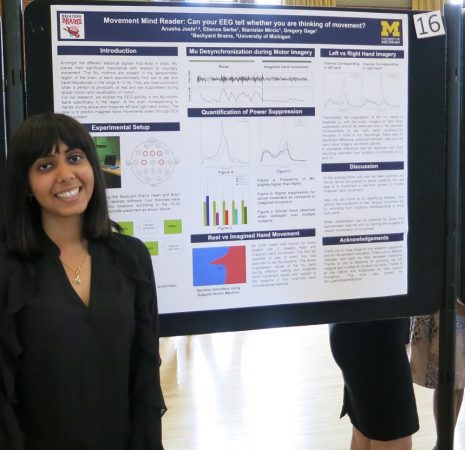

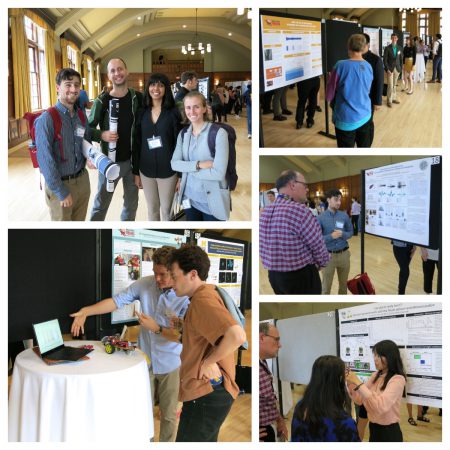

EducationThe Backyard Brains 2018 Summer Research Fellowship is coming to a close, but not before we get some real-world scientific experience in! Our research fellows are nearing the end of their residency at the Backyard Brains lab, and they are about to begin their tenure as neuroscience advocates and Backyard Brains ambassadors. The fellows dropped in […]

EducationThe Backyard Brains 2018 Summer Research Fellowship is coming to a close, but not before we get some real-world scientific experience in! Our research fellows are nearing the end of their residency at the Backyard Brains lab, and they are about to begin their tenure as neuroscience advocates and Backyard Brains ambassadors. The fellows dropped in […] -

FellowshipHello everyone! The previous two weeks have been an emotional and professional roller-coaster for me. It was tough saying goodbye to Etienne, who was such a lovely mentor for almost five weeks, but there was also the joy of welcoming Stanislav (our new mentor!), my parents from India visited me and then they left, I […]

FellowshipHello everyone! The previous two weeks have been an emotional and professional roller-coaster for me. It was tough saying goodbye to Etienne, who was such a lovely mentor for almost five weeks, but there was also the joy of welcoming Stanislav (our new mentor!), my parents from India visited me and then they left, I […] -

FellowshipOne of the most attractive things about a BYB Summer Fellowship is the chance to spend a summer in colorful Ann Arbor. We changed the program name from an internship to a fellowship because of the lasting connections made throughout the summer, and these connections are made possible by the things we all do together! […]

FellowshipOne of the most attractive things about a BYB Summer Fellowship is the chance to spend a summer in colorful Ann Arbor. We changed the program name from an internship to a fellowship because of the lasting connections made throughout the summer, and these connections are made possible by the things we all do together! […] -

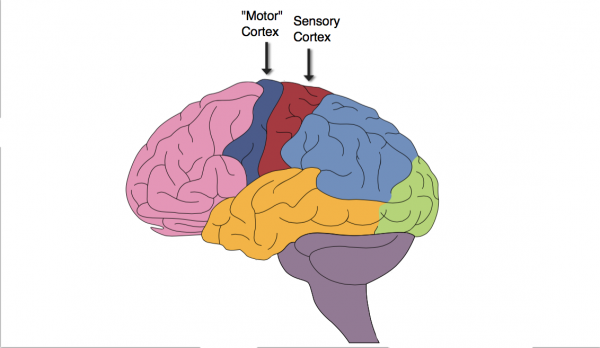

FellowshipHello! We are inching towards our goal of giving you a superpower! Last time, I was trying to find the mu rhythms, and I strongly think I may have found them. This consisted of two main steps. One was to find the right montage (electrode locations) which will help us see the mu rhythms. And […]

FellowshipHello! We are inching towards our goal of giving you a superpower! Last time, I was trying to find the mu rhythms, and I strongly think I may have found them. This consisted of two main steps. One was to find the right montage (electrode locations) which will help us see the mu rhythms. And […] -

FellowshipFresh, organic, locally sourced meditation researchLast Friday, Backyard Brains once again opened our doors (even wider–they’re always open during business hours!) to our fellow and aspiring citizen scientists as a part of this year’s Ann Arbor Tech Trek! Dozens of local tech companies had their doors open to the public that evening and we, like […]

FellowshipFresh, organic, locally sourced meditation researchLast Friday, Backyard Brains once again opened our doors (even wider–they’re always open during business hours!) to our fellow and aspiring citizen scientists as a part of this year’s Ann Arbor Tech Trek! Dozens of local tech companies had their doors open to the public that evening and we, like […] -

FellowshipRemember Professor Charles Francis Xavier? The founder and leader of X-men has phenomenal telepathic abilities. But, alas, he only exists in fiction! Or so we thought. What if we had the technology to make a part of Professor X’s abilities reality? We could channel the superpower of looking into people’s minds to know what movement […]

FellowshipRemember Professor Charles Francis Xavier? The founder and leader of X-men has phenomenal telepathic abilities. But, alas, he only exists in fiction! Or so we thought. What if we had the technology to make a part of Professor X’s abilities reality? We could channel the superpower of looking into people’s minds to know what movement […] -

EducationFrom left: Ben, Anusha, Yifan, Jessica, Aaron, Jess, Greg Gage (not a Fellow), Maria, Dan, Anastasiya, Molly, Ilya Meet the Fellows, See the Projects The fellows are off to a great start! This week has been focused on them getting their feet wet with our kits and learning about what we do here at Backyard Brains. Be […]

EducationFrom left: Ben, Anusha, Yifan, Jessica, Aaron, Jess, Greg Gage (not a Fellow), Maria, Dan, Anastasiya, Molly, Ilya Meet the Fellows, See the Projects The fellows are off to a great start! This week has been focused on them getting their feet wet with our kits and learning about what we do here at Backyard Brains. Be […]