-

EducationThe Backyard Brains 2018 Summer Research Fellowship is coming to a close, but not before we get some real-world scientific experience in! Our research fellows are nearing the end of their residency at the Backyard Brains lab, and they are about to begin their tenure as neuroscience advocates and Backyard Brains ambassadors. The fellows dropped in […]

EducationThe Backyard Brains 2018 Summer Research Fellowship is coming to a close, but not before we get some real-world scientific experience in! Our research fellows are nearing the end of their residency at the Backyard Brains lab, and they are about to begin their tenure as neuroscience advocates and Backyard Brains ambassadors. The fellows dropped in […] -

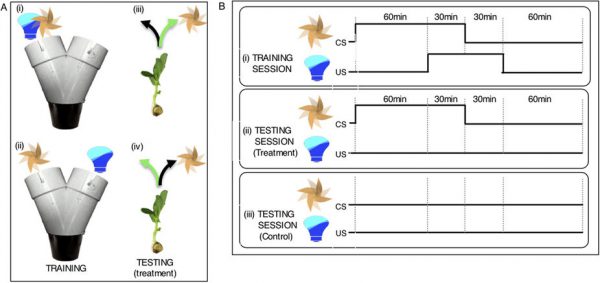

FellowshipStrange to be introducing a new project on my conclusion post, but it’s a cool one! While waiting for pea plant project parts to arrive, I revisited another project that Monica Gagliano had done with the Mimosa pudica: https://youtu.be/Xm5i53eiMkU?t=2m45s. For those of you too impatient to watch a video (like me!) the Mimosa pudica is a […]

FellowshipStrange to be introducing a new project on my conclusion post, but it’s a cool one! While waiting for pea plant project parts to arrive, I revisited another project that Monica Gagliano had done with the Mimosa pudica: https://youtu.be/Xm5i53eiMkU?t=2m45s. For those of you too impatient to watch a video (like me!) the Mimosa pudica is a […] -

FellowshipHello! There has been some trial and error since my last update. I started my experiment with Monica Gagliano’s protocol (overly simplified!): Grow seedlings, 48 of them: Get them used to 8 hours of light, 16 hours dark (circadian rhythm): Train them under decision covers for 3 days: Test them She had 48 of them. Unfortunately, each of those […]

FellowshipHello! There has been some trial and error since my last update. I started my experiment with Monica Gagliano’s protocol (overly simplified!): Grow seedlings, 48 of them: Get them used to 8 hours of light, 16 hours dark (circadian rhythm): Train them under decision covers for 3 days: Test them She had 48 of them. Unfortunately, each of those […] -

FellowshipOne of the most attractive things about a BYB Summer Fellowship is the chance to spend a summer in colorful Ann Arbor. We changed the program name from an internship to a fellowship because of the lasting connections made throughout the summer, and these connections are made possible by the things we all do together! […]

FellowshipOne of the most attractive things about a BYB Summer Fellowship is the chance to spend a summer in colorful Ann Arbor. We changed the program name from an internship to a fellowship because of the lasting connections made throughout the summer, and these connections are made possible by the things we all do together! […] -

FellowshipFresh, organic, locally sourced meditation researchLast Friday, Backyard Brains once again opened our doors (even wider–they’re always open during business hours!) to our fellow and aspiring citizen scientists as a part of this year’s Ann Arbor Tech Trek! Dozens of local tech companies had their doors open to the public that evening and we, like […]

FellowshipFresh, organic, locally sourced meditation researchLast Friday, Backyard Brains once again opened our doors (even wider–they’re always open during business hours!) to our fellow and aspiring citizen scientists as a part of this year’s Ann Arbor Tech Trek! Dozens of local tech companies had their doors open to the public that evening and we, like […] -

FellowshipMy project, if you remember (see previous post), is to train plants to associate fans with light and hopefully get them to grow in the direction of a fan after they’ve been trained. Radiolab has also done an awesome podcast on this. How hard can it be to set 48 of these up? I’ll split it into […]

FellowshipMy project, if you remember (see previous post), is to train plants to associate fans with light and hopefully get them to grow in the direction of a fan after they’ve been trained. Radiolab has also done an awesome podcast on this. How hard can it be to set 48 of these up? I’ll split it into […] -

FellowshipHi! I’m Jessica, a high school Biology/Anatomy&Physiology/Marine Biology/Forensics teacher in southern California. I’m the only high school teacher in this summer Fellowship of the Brain but hopefully I’ll make a good enough impression so they’ll invite more teachers in the future… after all, we ARE the market. The first week has been amazing. Besides feeling like I’m […]

FellowshipHi! I’m Jessica, a high school Biology/Anatomy&Physiology/Marine Biology/Forensics teacher in southern California. I’m the only high school teacher in this summer Fellowship of the Brain but hopefully I’ll make a good enough impression so they’ll invite more teachers in the future… after all, we ARE the market. The first week has been amazing. Besides feeling like I’m […] -

EducationFrom left: Ben, Anusha, Yifan, Jessica, Aaron, Jess, Greg Gage (not a Fellow), Maria, Dan, Anastasiya, Molly, Ilya Meet the Fellows, See the Projects The fellows are off to a great start! This week has been focused on them getting their feet wet with our kits and learning about what we do here at Backyard Brains. Be […]

EducationFrom left: Ben, Anusha, Yifan, Jessica, Aaron, Jess, Greg Gage (not a Fellow), Maria, Dan, Anastasiya, Molly, Ilya Meet the Fellows, See the Projects The fellows are off to a great start! This week has been focused on them getting their feet wet with our kits and learning about what we do here at Backyard Brains. Be […]