-

ExperimentRelated Post: High School Students Publish a Paper on Plant Physiology in a Notable Journal It’s tested and proven: Paramedics, firefighters, police officers and other first responders are almost twice as likely to develop PTSD (Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder) at some point in their lives than the rest of us. Still, many of them are either unaware […]

ExperimentRelated Post: High School Students Publish a Paper on Plant Physiology in a Notable Journal It’s tested and proven: Paramedics, firefighters, police officers and other first responders are almost twice as likely to develop PTSD (Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder) at some point in their lives than the rest of us. Still, many of them are either unaware […] -

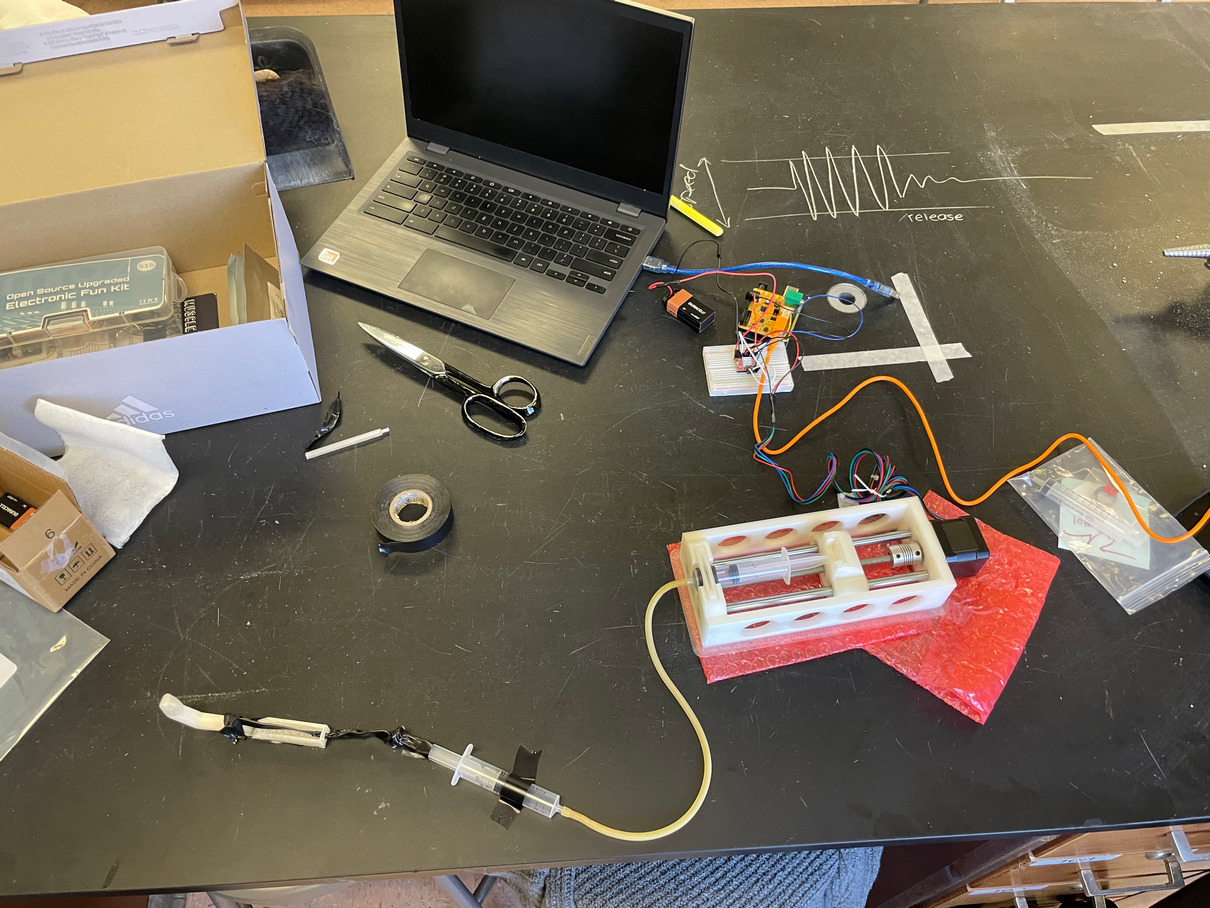

StudentsA pump made of two plastic syringes and a pushing block powered by a stepper motor, one of our Muscle SpikerShields and a 3D-printed base — that’s all that Kiley Branan, a high school senior from Indiana, needed to put together a prototype of a finger that you can open and close by flexing your […]

StudentsA pump made of two plastic syringes and a pushing block powered by a stepper motor, one of our Muscle SpikerShields and a 3D-printed base — that’s all that Kiley Branan, a high school senior from Indiana, needed to put together a prototype of a finger that you can open and close by flexing your […] -

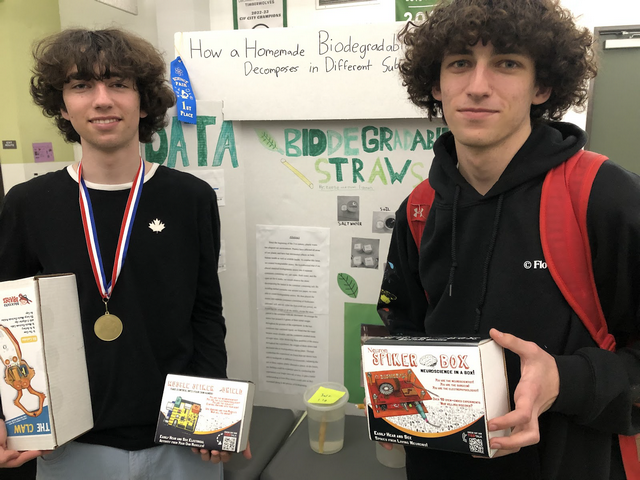

UncategorizedMany a high schooler has won a science fair or two using our neuroscience gear. But this science fair season, we decided to support the next generation of scientific innovators in a slightly different way: by donating prizes to the top projects at the Larchmont Charter High School Science Fair in Los Angeles! This event is […]

UncategorizedMany a high schooler has won a science fair or two using our neuroscience gear. But this science fair season, we decided to support the next generation of scientific innovators in a slightly different way: by donating prizes to the top projects at the Larchmont Charter High School Science Fair in Los Angeles! This event is […] -

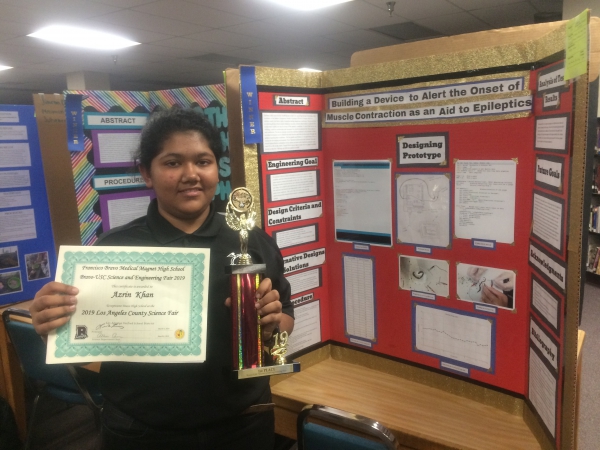

EducationMy name is Azrin Khan and I am currently a junior (11th grade) in Francisco Bravo Medical Magnet Senior High School in California. My purpose is to build a device which will alert humans when they are going to have muscle cramps, and it will keep a record of the intensity of the cramp and […]

EducationMy name is Azrin Khan and I am currently a junior (11th grade) in Francisco Bravo Medical Magnet Senior High School in California. My purpose is to build a device which will alert humans when they are going to have muscle cramps, and it will keep a record of the intensity of the cramp and […] -

EducationThe Third Thumb An 8th Grader’s Exploration in DIY Neuroprosthetics Several months ago, a crowdfunded classroom got their hands on several of our neuroprosthetic kits – like The Claw and the Muscle SpikerShield Bundle. This allowed students in Nokomis Regional schools to begin experimenting with hands-on neuroscience experiments! One of the students, 8th grader Kaiden K., was interested in developing a prosthetic, but […]

EducationThe Third Thumb An 8th Grader’s Exploration in DIY Neuroprosthetics Several months ago, a crowdfunded classroom got their hands on several of our neuroprosthetic kits – like The Claw and the Muscle SpikerShield Bundle. This allowed students in Nokomis Regional schools to begin experimenting with hands-on neuroscience experiments! One of the students, 8th grader Kaiden K., was interested in developing a prosthetic, but […] -

EducationHello everyone. My name is Pranav Senthilkumar and I am a junior at Mission San Jose High School in Fremont, CA (SFO Bay Area) For my project at the Alameda County Science fair last year, I designed a neuroprosthetic device using the original SpikerBox and the Human Neuroprosthetic kit. What is a Neuroprosthetic, and how does […]

EducationHello everyone. My name is Pranav Senthilkumar and I am a junior at Mission San Jose High School in Fremont, CA (SFO Bay Area) For my project at the Alameda County Science fair last year, I designed a neuroprosthetic device using the original SpikerBox and the Human Neuroprosthetic kit. What is a Neuroprosthetic, and how does […] -

EducationTwo students from Stone Magnet Middle School in Florida, with the guidance of their teacher, Richard Regan, decided to make their science projects in neuroscience. We feel we’ve accomplished our core mission by just being able to write this statement: that today it is an option for students in middle school to make neuroscience experiments […]

EducationTwo students from Stone Magnet Middle School in Florida, with the guidance of their teacher, Richard Regan, decided to make their science projects in neuroscience. We feel we’ve accomplished our core mission by just being able to write this statement: that today it is an option for students in middle school to make neuroscience experiments […]