-

EducationIn an article we previously published in June 2022 about our scientific paper that dealt with play behavior in fish, I concluded at the end of the article: “I think it is possible for novices and high school students to publish papers (and it is the dream and goal of our team)… That is why we […]

EducationIn an article we previously published in June 2022 about our scientific paper that dealt with play behavior in fish, I concluded at the end of the article: “I think it is possible for novices and high school students to publish papers (and it is the dream and goal of our team)… That is why we […] -

EducationYou never know what might capture a students’ attention and passion… Maybe the recent photo of a black hole inspires a student to learn about astrophysics, or maybe an experiment involving cockroaches inspires a student to want to learn more about neuroscience! Recently, we heard word from two graduating high school seniors in Ohio who started […]

EducationYou never know what might capture a students’ attention and passion… Maybe the recent photo of a black hole inspires a student to learn about astrophysics, or maybe an experiment involving cockroaches inspires a student to want to learn more about neuroscience! Recently, we heard word from two graduating high school seniors in Ohio who started […] -

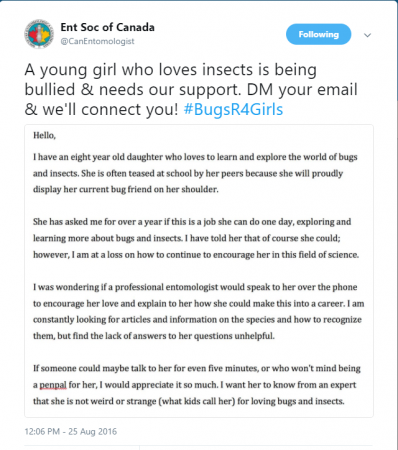

EducationLast year, Sophia, 8, a young entomologist, was being bullied at school because of her excitement for and interest in bugs and science. Now, just one year later, she has been published as a junior author in the Annals of the Entomological Society of America! With a craving which couldn’t be curbed to capture, observe, befriend, […]

EducationLast year, Sophia, 8, a young entomologist, was being bullied at school because of her excitement for and interest in bugs and science. Now, just one year later, she has been published as a junior author in the Annals of the Entomological Society of America! With a craving which couldn’t be curbed to capture, observe, befriend, […]